Why Are Startups Hard?

Published November 15, 2024

It's not the hours - many jobs require insane hours. It's not the stress - there are many stressful jobs. So what makes startups so uniquely challenging?

This was a speech given to Motion in a Cancun company offsite on July, 2024.

At the time, Motion had experienced unprecedented growth. Most people in the room had only ever seen hyper-growth. But I predicted that those fun times would end, and I wanted to brace the company for the coming period of difficulty. This proved especially prescient, as the growth did in fact stop nearly to the exact month I predicted. We then had to rally and pivot the company to find the next S-curve.

Here is the video, unedited.

Below are the raw slides:

If you prefer reading to watching a video, the ~raw text is below.

“For years milers had been striving against the clock, but the elusive four minutes had always beaten them,” he notes. “It had become as much a psychological barrier as a physical one. And like an unconquerable mountain, the closer it was approached, the more daunting it seemed.”

— Practically Radical by William C Taylor

For decades, everyone thought the 4 minute mile was something impossible. Experts had long theorized the ideal conditions: a larger track (they had a harder type of track that made it easier to kick off of), a cool day, maybe mid 70s, so the athletes wouldn’t over heat. No rain, of course, and so on and so forth.

In May 1954, Sir Roger Bannister breaks the 4 minute mile. The best part is that he does it in all the “wrong” conditions. A semi drizzly day in a no name track in front of a few thousand people.

And over night, it becomes possible. Perhaps more interestingly, it quickly became the norm. In the next 3 months, three more 4 minute miles took place — the second being Australian John Landy. The very next year, 1955, three runners do it in the same race. By 1964, we have the first high schooler to do it. And as of January 1, 2024, 732 Americans and over 1800 people globally have done what was supposed to be impossible.

Was there a sudden growth spurt in human evolution? Was there a genetic engineering experiment that created a new race of super runners? No. What changed was the mental model. The runners of the past had been held back by a mindset that said they could not surpass the four-minute mile. When that limit was broken, the others saw that they could do something they had previously thought impossible.

— The Power of Impossible Thinking by Yoram Wind and Colin Crook

It’s important to know that there wasn’t some secret technique. If there were, perhaps Bannister would have been the only one to do it for quite some time. But that’s not what happened. He does it, and overnight, someone on the other side of the world stands up and believes that he can do it, too.

This same phenomenon — the mere act of seeing something be done inspiring others — is something I’m going to refer to henceforth as the Bannister Effect. Perhaps this case is rather trivial. Just run faster, what more can there be? Interestingly, this same effect takes place even in academic settings.

Kagle is a machine learning and data science competition platform, and Francois is a Google Deep Mind researcher.

We see the same example in business:

There was a marketing channel we had looked at, but we put it on the shelf. Then I heard a whisper that someone else using this channel was crushing it. Now, I didn’t know what they were doing, their technique, and I don’t know how much they’re crushing it. I just heard enough to know that they are crushing it. And immediately, just the knowledge that someone else was crushing it, got us fired up — and over the weekend we did 30 grand of revenue on this one channel.

— Shaan Puri, CEO of Babi (Acquired by Twitch)

This ability to inspire people to believe in and execute on the impossible is present in many incredibly successful entrepreneurs and leaders. But one person embodied this phenomenon more than anyone else: Steve Jobs. So much so that he has his own wikipedia entry dedicated to this exact phenomenon.

Then they did an iMac and an iPod nano in anodized aluminum, which meant that the metal had to be put in an acid bath and electrified so that its surface oxidized. Jobs was told it could not be done in the quantities he needed, so he had a factory built in China to handle it… “Ruby and others said it was impossible, but I wanted to do it.”

— Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

How quickly we forget that, at the time, conventional wisdom was that a consumer product could never be made out of aluminum. It simply wasn’t sturdy enough, and it would scratch too easily. Best to leave that stuff for disposables like soda cans or lightweight airplane materials. Steve was determined to prove everyone, even his own reports, wrong.

Apple was roundly criticized by everyone when they first announced the Apple Store concept. The whole point of technology was to have high margins. Why would anyone with any ounce of business brain ever go into retail? That was always a losing proposition, right?

Even Apple’s own former execs thought this was crazy.

Apple’s problem is that it still believes the way to grow is serving caviar in a world that seems pretty content with cheese and crackers.

— John Graziano, Apple’s former CFO

The famous retail “expert” [David Goldstein])(https://sensemktg.com/tag/retail-experience/) had to weigh in:

I give them 2 years before they’re turning off the lights on a very expensive and very painful mistake.

On a per square-foot basis, Apple makes $5,500 from its Apple Stores. Tiffany’s only makes $3,000. (Third place is Ikea, at $1,800). Apple is now the best retailer in human history, and it’s not close.

After conquering aluminum, Jobs (and Ive) wanted to turn to glass. The problem, was there was no glass at the time that was both lightweight and durable enough. Until, he heard of a rumor of a beta product produced in the 60s that had since been shelved. It was called Gorilla Glass, and it was purely theoretical. It had never been made outside of a lab setting, let alone manufactured in large quantities.

This turned Jobs around, and he said he wanted as much Gorilla glass as Corning could make in 6 months. “We don’t have that capacity. None of our plants make that glass now!” “Don’t be afraid… Yes, you can do it,” Jobs said, unblinking. “Get your mind around it, you can do it.” “We did it in under 6 months”, Weeks said.

— Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

It ends the same way every single time. The supposedly impossible target is reached. Note that in this quote, Weeks is the then-CEO of Korning Glass, an expert on the chemistry and manufacturing process. It’s one thing if Jobs was proving the ignorant masses wrong. But in every example, he’s proving experts in their field who clearly know more than him to be incorrect.

Many things in life are hard. But the reason startsup are uniquely hard is that you have to believe in the impossible, even when there is no evidence. You’re going on pure faith. It’s the difference between being the first human in history to run a 4 minute mile — when all the experts are telling you it’s impossible — and being the 2812th person to do it. Still impressive, just not quite the same. It’s the difference between running a marathon (very impressive, I certainly can’t do it) and winning the Last Man Standing ultramarathon, where there’s no set distance. You just keep going until everyone else gives up. In the end, your faith is what gets you to the finish line.

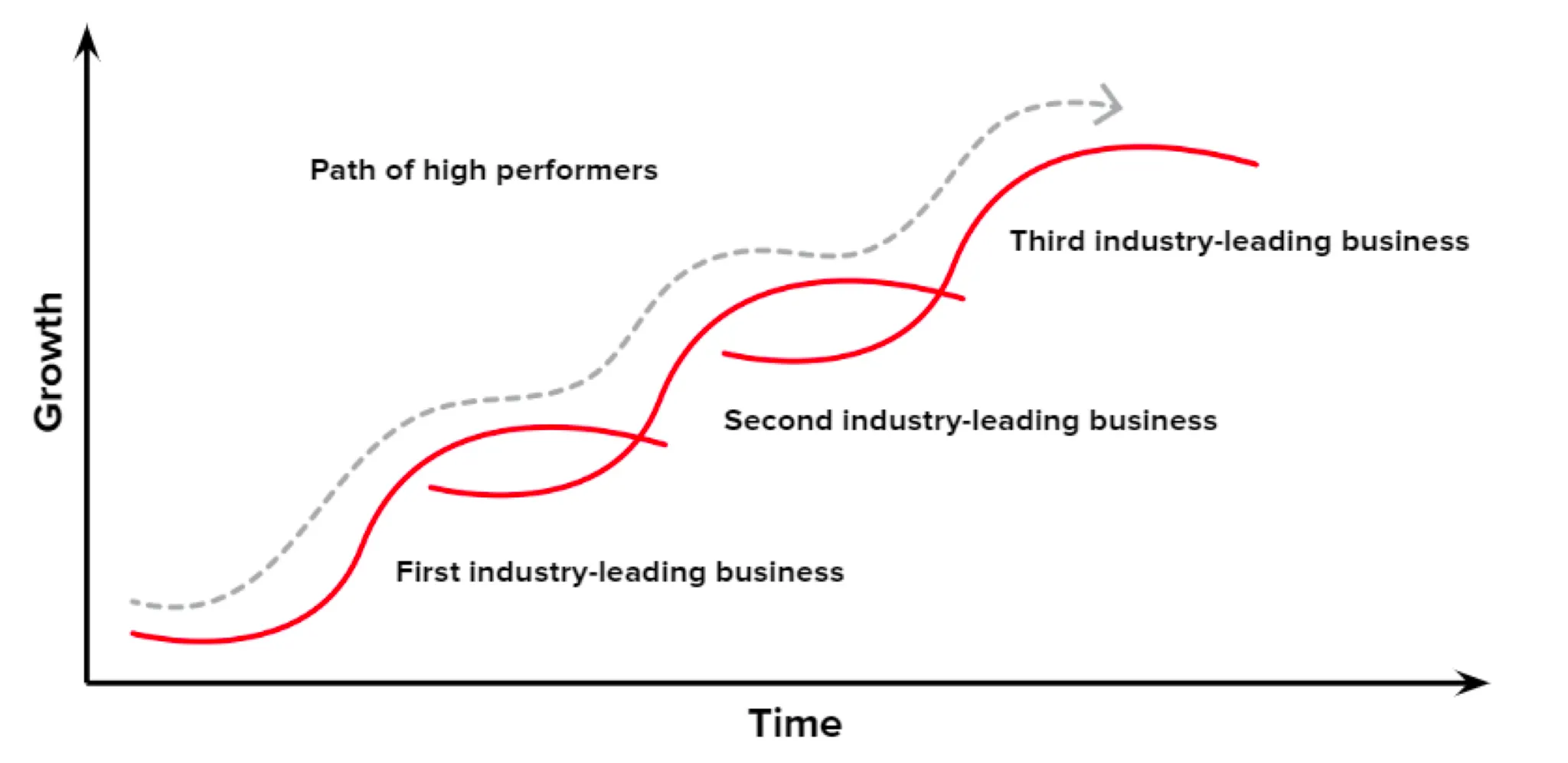

We like to think of progress as linear, but that’s simply not true in most things in life. We bang our head against the wall, scratching and clawing, desperate to find something that gives us leverage over the market. For long periods of time, this looks like flat, or even negative, growth. These challenging flats are expected in any startup. Once we find that piece of leverage, we start to extract value as fast as we possibly can. We go all in, and that supercharges our growth into a very familiar S-curve. But the curve doesn’t go on forever.

At some point, we hit another flat. Maybe the industry has changed, and our solution no longer works. Perhaps customer expectations have shifted. Or maybe we’ve simply outgrown the market, and the new, larger markets require a new approach. Regardless of whether you’re winning (outgrowing the market) or failing (technology has shifted under you), the flat part of the S-curve, where all hope seems lost, is coming. The only question is what are we going to do when we get there. Are we going to cry and complain about how hard life is? Or are we going to believe in something greater.

Whenever we’re looking at businesses, we see them on an S curve. It’s very difficult to imagine new S curves, but the very best businesses will continuously create new S curves and new opportunities.

— Tom Hulme from Google Ventures, on why VCs underestimate the size of winners

Note that Hulme is talking about Twilio, a company in which he was a seed-stage investor, and he thought in the best case he imagined was a $500 million outcome. (It was $12 billion.) Even true believers in a business have a hard time with the Bannister Effect because everyone believes that innovation is a Newton-apple scenario; a new idea hits you like a lightning strike, and it’s pure luck. You can never replicate that again. But we know that’s simply not true. The best companies will continue to ram through those flat troughs on the S-curve, continue to breakdown walls, and continue to find new opportunities.

This is the most exciting time to be at Motion! We are finally doing brand new stuff that nobody has done before. Motion in 2021-2022 was a fucking calendar app. There’s two dozen of those. Motion in 2022-2023 was a shitty PM tool that was missing features. Today? Nobody has flows. Nobody has notes that can instantly turn into tasks or projects. We’re building brand new stuff on the edge of human knowledge, and that’s incredibly exciting.

But it also has a cost. Nobody can tell you with certainty how long this will take, or even whether we’ll succeed. And the stakes are high. If you take a trip to the South Pole and you get lost, don’t expect to make it back in one piece. If we don’t figure this out, we die.

Doing the impossible shouldn’t scare you. The history of Motion has been doing the impossible over and over again.

- Harry was rejected by 180 seed investors. 99.99% of companies die right there.

- 1 year in Motion isn’t going well, Ethan and Harry say bye to their wives and live together with Omid in a tiny apartment, sleeping on the floor.

- It’s still not going well, and they tell themselves if they don’t get 100k ARR in 3 months, they’ll all quit. At the end of 3 months, 110k ARR. Motion barely survives.

- Every single investory told me “Aren’t you guys just Reclaim / Clockwise / Sunsama / Akiflow / Amie / Hoop / VimCal” - we have more revenue than all of them combined

- We scaled marketing to $20M/year with just Gary and Olesya; they generate multiple winners every single week and manage hundreds of creators. We were told this would take a team of ten. People always email in Gary and ask how is this even possible.

- SEO trial starts increased 5x in June, and those trial starts are converting at 60% (usual is 40%)

- Bishop took over all of support - he hired, trained, and managed 30 support agents all by himself. No prior experience. When he first took over the role we tried to hire across 3 different countries, 4 different time zones, Bishop worked from 6am the first day to 7PM the next day, STRAIGHT.

- We also have incredibly high standards with insane retention. Support agents that were leads at other BPOs are usually fired in the first two weeks. Typical retention is 50% churnover ever year. We’re at 17%. We went from zero to world class support org in one year with Bishop

- This past January we had a growth emergency. As a response we did our entire 6 month growth road map in three weeks. Ethan, Maddy, myself, Omid all worked weekends and just plowed through

- Will does 4 people’s jobs - HR, accounting, legal, FP&A

- We got buy in from 6 people and moved them into a hacker house for 3 months working 9am to 11pm, 6 days a week at a series C company

- 1 person rewrote the entire mobile app

- Moving to daily deploys despite at the time having an emergency twice a week; I was told this would be the death of Motion and cause numerous emergencies

- Desktop app was launched by one person, in 7 weeks

- Killing the chrome extension was supposed to kill our business, because we’re just a chrome extension company; since we killed the extension, our revenue has 20x-ed

- Launching our own PM tool instead of just integrating with competitors; this was “pure arrogance” as one of my friends told me.

- We moved databases with zero data loss, in one hour of downtime. That was one person.

- Hiring all of you! We have an absurdly stacked team relative to any startup of our size. Recruiting any of you was supposed to be impossible.

I’m tired of losers telling me what is and isn’t possible. You know the types. The professional nonachievers who poo-poo everything anyone does because they’re too chicken-shit to actually take risk and try anything in life. So they make themselves feel better by shitting on everything everyone else does. Stop listening to them. Those clowns will never change the world. They’ll never do anything hard, let alone impossible.

The issue with their ideas was that we weren’t facing a market problem. The customers were buying; they just weren’t buying our product. This was not a time to pivot. So I said the same thing to every one of them: “There are no silver bullets for this, only lead bullets.” They did not want to hear that, but it made things clear: we had to build a better product. There was no other way out. No window, no hole, no escape hatch, no backdoor. We had to go through the front door and deal with the big, ugly guy blocking it. Lead bullets… There comes a time in every company’s life where it must fight for its life. If you find yourself running when you should be fighting, you need to ask yourself: “If our company isn’t good enough to win, then do we need to exist at all?”

— The Hard Thing About Hard Things by Ben Horowitz

When times are hard, it’s tempting to try and come up with a silver bullet. If only I can change the strategy here, or consult with an expert that will unlock a big winner there. Resist this temptation at all costs. We’ve all been there. Maybe the new year rolls around, and we’re not losing as much weight as we’d like. Oh this year I’ll try paleo. Or keto. Or vegan. It’s never the pivot. It’s never the diet. Instead, we overlook the most simple solution: Up your intensity.

Most of the time, hard problems require hard solutions. That doesn’t mean the solution doesn’t exist. Accept that the solution is hard, up your intensity, and run through that god damn wall. Most people don’t know what true intensity looks like. This isn’t a statement about their capability. Even incredibly capable people often don’t know what real intensity is!

This motherfucker Kobe was already drenched in sweat, and we was like, ‘Yeah, he different.’

— Lebron James recalls Kobe Bryant’s mentality during the Olympics; other teammates were enthralled by Kobe’s work ethic.

Lebron, who is undeniably a better all time basketball player than Kobe, did not know what true intensity was until he worked with Kobe for the first time. If you’re new to Motion, it’s highly likely you don’t know true intensity either. That is not a value judgement on your capabilities. Rather, it’s a recognition that most of the world does not operate the way we do; that is why we will win. Our culture provides us a unique pain tolerance to push through the hard problems to the S-curve on the other side.

Here are some of my favorite examples of true intensity.

-

Jesse Itzler, like many of us, wanted to get in shape. Most of us start with a gym membership. He started by hiring a Navy Seal to come live in his house, and said he would jump when the Seal said jump, run when the Seal said run. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he got in really good shape. That’s intensity. (That Seal was David Goggins, before he was famous.)

-

When starting a business, most of us would ask our friends or customers try it out. They’ll probably reply with something like “sure thing, just send me the email.” And of course, they never actually do it. Patrick Collison would simply install it for them, right there on their laptop. A great example of true intensity.

-

Sylvester Stallone really wanted to be an actor; the only problem was that nobody could cast him. His wife was pregnant, and they had barely enough money for three days. So locked himself in the room, disconnected the phone, painted his windows black so he wouldn’t know what time it was, and wrote a script to his own movie in those 3 days. He had to sell his dog just to make ends meet. Intense enough yet? (He bought his dog back once he was successful.)

Physics is the law, everything else is a recommendation

— Elon Musk

We’re here to do incredible, impossible things. We’re here to make a tool that reshapes knowledge work and fundamentally jump start the world’s productivity. We’re out here on the frontier of human knowledge. It’s an incredibly exciting time for Motion, and I’m so excited to have all of you here.

Exploration is the engine that drives innovation. Innovation drives economic growth. So let’s all go exploring.

— Edith Widder, American oceanography and marine biologist

This post was shamelessly inspired by this rather excellent episode of My First Million podcast.